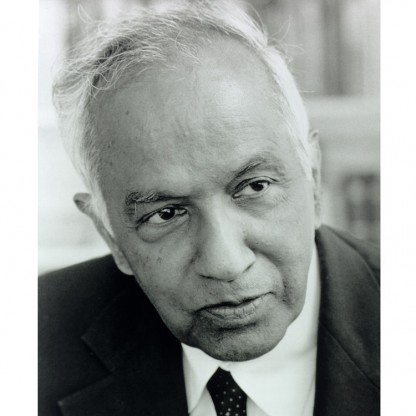

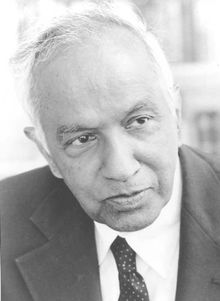

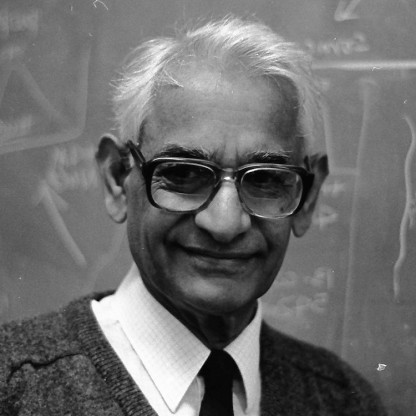

Chandrasekhar was tutored at home until the age of 12. In middle school his father would teach him Mathematics and Physics and his mother would teach him Tamil. He later attended the Hindu High School, Triplicane, Madras during the years 1922–25. Subsequently, he studied at Presidency College, Madras from 1925 to 1930, writing his first paper, "The Compton Scattering and the New Statistics", in 1929 after being inspired by a lecture by Arnold Sommerfeld. He obtained his bachelor's degree, B.Sc. (Hon.), in physics, in June 1930. In July 1930, Chandrasekhar was awarded a Government of India scholarship to pursue graduate studies at the University of Cambridge, where he was admitted to Trinity College, Cambridge, secured by R. H. Fowler with whom he communicated his first paper. During his travels to England, Chandrasekhar spent his time working out the statistical mechanics of the degenerate electron gas in white dwarf stars, providing relativistic corrections to Fowler's previous work (see Legacy below).