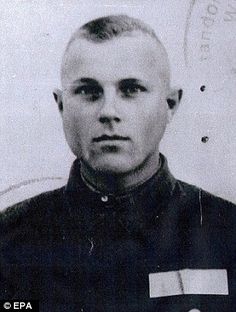

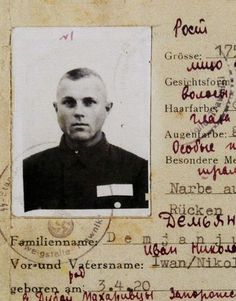

He survived the ordeal, and volunteered to be sent to the Trawniki concentration camp division utilized for the training of Hiwi guards recruited from Soviet POWs, later allegedly serving in Majdanek, Sobibor and Flossenbürg Nazi camps, and during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Demjanjuk claims that, in early 1945, he joined the Russian Liberation Army (Russian: Russkaya osvoboditel'naya armiya, Русская освободительная армия, abbreviated in Cyrillic as РОА, in Latin as ROA, also known as the Vlasov army), led by Andrey Vlasov, which was organized by Nazi Germany to fight against the Soviet Red Army. Many Soviet prisoners of war volunteered to serve under the Nazi command in order to get out of the POW camps, where 2.8 million Soviet POWs died through starvation, exposure, and summary execution. Such non-German volunteers that served in Germany's foreign legions were referred to by the German command as Freiwillige. the German word for volunteer, and also as Hilfswilliger, literally one willing to help, often shortened to Hiwi, in auxiliary non-combat paramilitary and civilian capacities. According to Allied general Lt. Gen. Władysław Anders, by 1942, there were about a million such volunteers from the USSR alone.