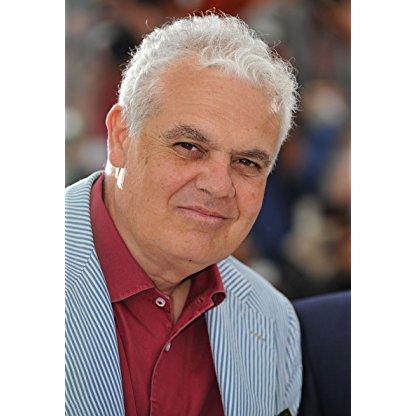

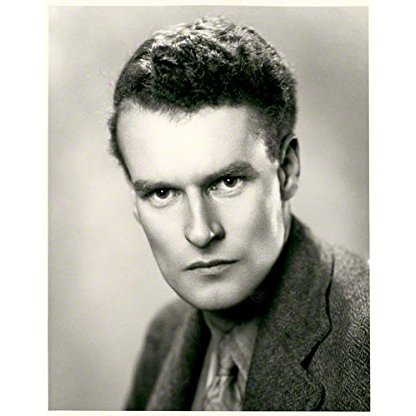

Éric Rohmer was born on March 21, 1920 in Tulle, Corrèze, France, France, is Director, Writer, Actor. Admirers have always had difficulty explaining Éric Rohmer's "Je ne sais quoi." Part of the challenge stems from the fact that, despite his place in French Nouvelle Vague (i.e., New Wave), his work is unlike that of his colleagues. While this may be due to the auteur's unwillingness to conform, some have argued convincingly that, in truth, he has remained more faithful to the original ideals of the movement than have his peers. Additionally, plot is not his foremost concern. It is the thoughts and emotions of his characters that are essential to Rohmer, and, just as one's own states of being are hard to define, so is the internal life of his art. Thus, rather than speaking of it in specific terms, fans often use such modifiers as "subtle," "witty," "delicious" and "enigmatic." In an interview with Dennis Hopper, Quentin Tarantino echoed what nearly every aficionado has uttered: "You have to see one of [his movies], and if you kind of like that one, then you should see his other ones, but you need to see one to see if you like it."Detractors have no problem in expressing their displeasure. They use such phrases as "tedious like a classroom play," "arty and tiresome" and "donnishly talky." Gene Hackman, as jaded detective Harry Moseby in Night Moves (1975), delivered a now famous line that sums up these feelings: "I saw a Rohmer film once. It was kind of like watching paint dry." Undeniably, his excruciatingly slow pace and apathetic, self-absorbed characters are hallmarks, and, at times, even his greatest supporters have made trenchant remarks in this regard. Said critic Pauline Kael, "Seriocomic triviality has become Rohmer's specialty. His sensibility would be easier to take if he'd stop directing to a metronome." In that his proponents will quote attacks on him, indeed Rohmer may be alone among directors. They revel in the fact that "nothing of consequence" happens in his pictures. They are mesmerized by the dense blocks of high-brow chatter. They delight in the predictability of his aesthetic. Above all, however, they are touched by the honesty of a man who, uncompromisingly, lays bear the human soul and "life as such."Who is Eric Rohmer? Born Jean-Marie Maurice Scherer on December 1, 1920 in Nancy, a small city in Lorraine, he relocated to Paris and became a literature teacher and newspaper reporter. In 1946, under the pen name Gilbert Cordier, he published his only novel, "Elizabeth". Soon after, his interest began to shift toward criticism, and he began frequenting Cinémathèque Français (founded by archivist Henri Langlois) along with soon-to-be New Wavers Jean-Luc Godard, Jacques Rivette, Claude Chabrol and François Truffaut. It was at this time that he adopted his pseudonym, an amalgam of the names of actor/director Erich von Stroheim and novelist Sax Rohmer (author of the Fu Manchu series.) His first film, Journal d'un scélérat (1950), was shot the same year that he founded "Gazette du Cinema" along with Godard and Rivette. The next year, Rohmer joined seminal critic André Bazin at "Cahiers du Cinema", where he served as editor-in-chief from 1956 to 1963. As Cahiers was an influential publication, it not only gave him a platform from which to preach New Wave philosophy, but it enabled him to propose revisionist ideas on Hollywood. An example of the latter was "Hitchcock, The First Forty-Four Films", a book on which he collaborated with Chabrol that spoke of Alfred Hitchcock in highly favorable terms.Rohmer's early forays into direction met with limited success. By 1958, he had completed five shorts, but his sole attempt at feature length, a version of La Comtesse de Ségur's "Les Petites filles modèles", was left unfinished. With Le signe du lion (1962), he made his feature debut, although it was a decade before he achieved recognition. In the interim, he turned out eleven projects, including three of his "Six contes moraux" (i.e., moral tales), films devoted to examining the inner states of people in the throes of temptation. La boulangère de Monceau (1963) and La carrière de Suzanne (1963) are unremarkable black-and-white pictures that best function as blueprints for his later output. They also mark the beginning of a business partnership with Barbet Schroeder, who starred in the former of the two. La collectionneuse (1967), his first major effort in color, has been mistaken for a Lolita movie; on a deeper plane, it questions the manner in which one collects or rejects experience. Rohmer's first "hit" was Ma nuit chez Maud (1969), which was nominated for two Oscars and won several international awards. It continues to be his best-known work. In it, on the eve of a proclaiming his love to Francoise, his future wife, the narrator spends a night with a pretty divorcée named Maud. Along with a friend, the two have a discussion on life, religion and Pascal's wager (i.e., the necessity of risking all on the only bet that can win.) Left alone with the sensual Maud, the narrator is forced to test his principles. The final parts in the series, Le genou de Claire (1970) and L'amour l'après-midi (1972) are mid-life crisis tales that cleverly reiterate the notion of self-restraint as the path to salvation."Comedies et Proverbs," Rohmer's second cycle, deals with deception. La femme de l'aviateur (1981) is the story a naïve student who suspects his girlfriend of infidelity. In stalking her ex-lover and ultimately confronting her, we discover the levels on which he is deceiving himself. Another masterpiece is Pauline à la plage (1983), a seaside film about adolescents' coming-of-age and the childish antics of their adult chaperones. Of the remaining installments, Le rayon vert (1986) and L'ami de mon amie (1987) are the most appealing. The director's last series is known as "Contes des quatre saisons" (i.e., Tales of the Four Seasons), which too presents the dysfunctional relationships of eccentrics. In place of the social games of "Comedies et Proverbs", though, this cycle explores the lives of the emotionally isolated. Conte de printemps (1990) and Conte d'hiver (1992) are the more inventive pieces, the latter revisiting Ma Nuit chez Maud's "wager." Just as his oeuvre retraces itself thematically, Rohmer populates it with actors who appear and reappear in unusual ways. The final tale, Conte d'automne (1998), brings together his favorite actresses, Marie Rivière and Béatrice Romand. Like "hiver," it hearkens back to a prior project, Le beau mariage (1982), in examining Romand's quest to find a husband.Since 1976, Rohmer has made various non-serial releases. 4 aventures de Reinette et Mirabelle (1987) and Les rendez-vous de Paris (1995), both composed of vignettes, are tongue-in-cheek morality plays that merit little attention. The lush costume drama Die Marquise von O... (1976), in contrast, is an excellent study of the absurd formalities of 18th century aristocracy and was recognized with the Grand Prize of the Jury at Cannes. His other period pieces, regrettably, have not been as successful. Perceval le Gallois (1978), while original, is a failed experiment in stagy Arthurian storytelling, and the beautifully dull L'anglaise et le duc (2001) is equally unsatisfying for most fans of his oeuvre. Nonetheless, the director has demonstrated incredible consistency, and that he was able to deliver a picture of this caliber so late in his career is astounding. The legacy that this man has bestowed upon us rivals that of any auteur, with arguably as many as ten tours de force over the last four decades. Why, then, is he the least honored among the ranks of the Nouvelle Vague and among all cinematic geniuses?Stories of Rohmer's idiosyncrasies abound. An ardent environmentalist, he has never driven a car and refuses to ride in taxis. There is no telephone in his home. He delayed the production of Ma Nuit chez Maud for a year, insisting that certain scenes could only be shot on Christmas night. Once, he requested a musical score that could be played at levels inaudible to viewers. He refers to himself as "commercial," yet his movies turn slim profits playing the art house circuit. Normally, these are kinds of anecdotes that would endear a one with the cognoscenti. His most revealing quirk, however, is that he declines interviews and shuns the spotlight. Where Hitchcock, for instance, was always ready to talk shop, Rohmer has let his films speak for themselves. He is not worried about WHAT people think of them but THAT, indeed, they think.It would be dangerous to supplant the aforementioned "je ne sais quoi" with words. Without demystifying Rohmer's cinema, still there are broad qualities to which one may point. First, it is marked by philosophical and artistic integrity. Long before Krzysztof Kieslowski, Rohmer came up with the concept of the film cycle, and this has permitted him to build on his own work in a unique manner. A devout Catholic, he is interested in the resisting of temptation, and what does not occur in his pieces is just as intriguing as what occurs. Apropos to the mention of his spirituality is his fascination with the interplay between destiny and free will. Some choice is always central to his stories. Yet, while his narrative is devoid of conventionally dramatic events, he shows a fondness for coincidence bordering on the supernatural. In order to maintain verisimilitude, then, he employs more "long shots" and a simpler, more natural editing process than his contemporaries. He makes infrequent use of music and foley, focusing instead on the sounds of voices. Of these voices, where his narrators are male (and it is ostensibly their subjective experience to which we are privy), his women are more intelligent and complex than his men. Finally, albeit deeply contemplative, Rohmer's work is rarely conclusive. Refreshingly un-Hollywood, rather than providing an escape from reality, it compels us to face the world in which we live.

Éric Rohmer is a member of Director